2. Understanding global supply chains

What is a supply chain?

A supply chain is made up of all the stages involved in the production and sale of a specific product. (Christian, Evers and Barrientos, 2013) The chain follows the product from its source as raw material to its final destination in a shop or warehouse. Global supply chains have become commonplace in many industries over the past 30 years. Under such systems the design, marketing and sales work is generally carried out in the wealthy economies of Europe, North America and Asia, while the manufacturing of goods is largely carried out in ‘developing’ countries in Asia, Africa and the Americas. The links in the supply ‘chain’ are all the steps that begin with growing or extracting raw materials (cotton, iron, oil, etc.) and end with the sale of the finished products to end users by the company at the top of the supply chain – often called the ‘lead’ company. Regional value chains are also gaining growing importance, particularly in South America and in Africa - e.g. Chile or Brazil exporting agricultural products to neighbouring countries.

In some industries, the lead company (or a subsidiary) owns some or all of the links in the supply chain. This often happens when quality control is very important, or the lead company has developed special manufacturing processes that they do not want competitors to access. In these kinds of supply chains, it is easier to identify the lead company as ultimately responsible for the welfare and rights of workers.

What is a supply chain?

...the term “global supply chains” refers to the cross-border organization of the activities required to produce goods or services and bring them to consumers through inputs and various phases of development, production and delivery. This definition includes foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational enterprises (MNEs) in wholly owned subsidiaries or in joint ventures in which the MNE has direct responsibility for the employment relationship. It also includes the increasingly predominant model of international sourcing where the engagement of lead firms is defined by the terms and conditions of contractual or sometimes tacit arrangements with their suppliers and subcontracted firms for specific goods, inputs and services. (ILO 2016, p.1)

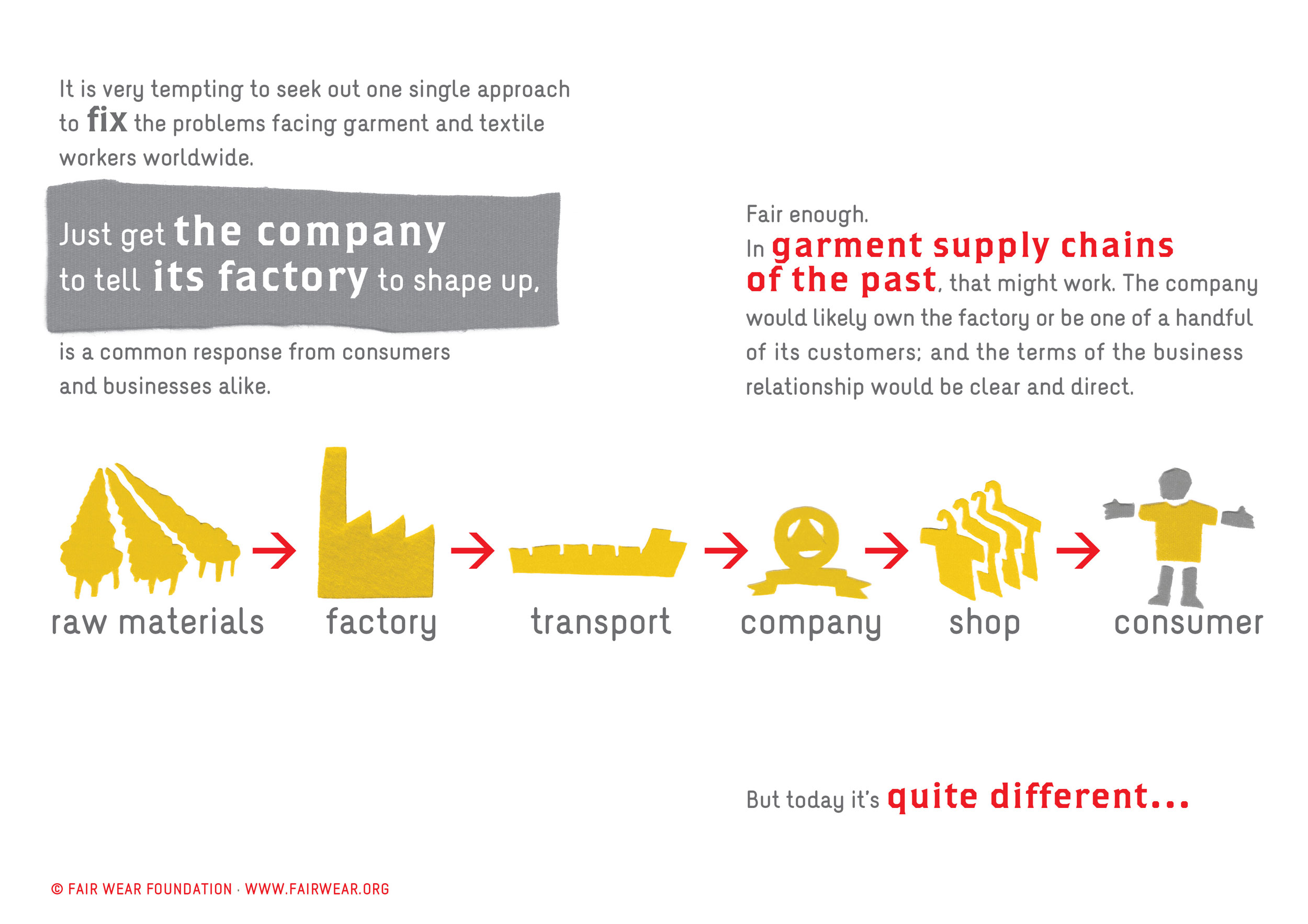

Chart 1 presents a simple supply chain model where the lead company either owns each stage of the supply chain or they know who the suppliers are.

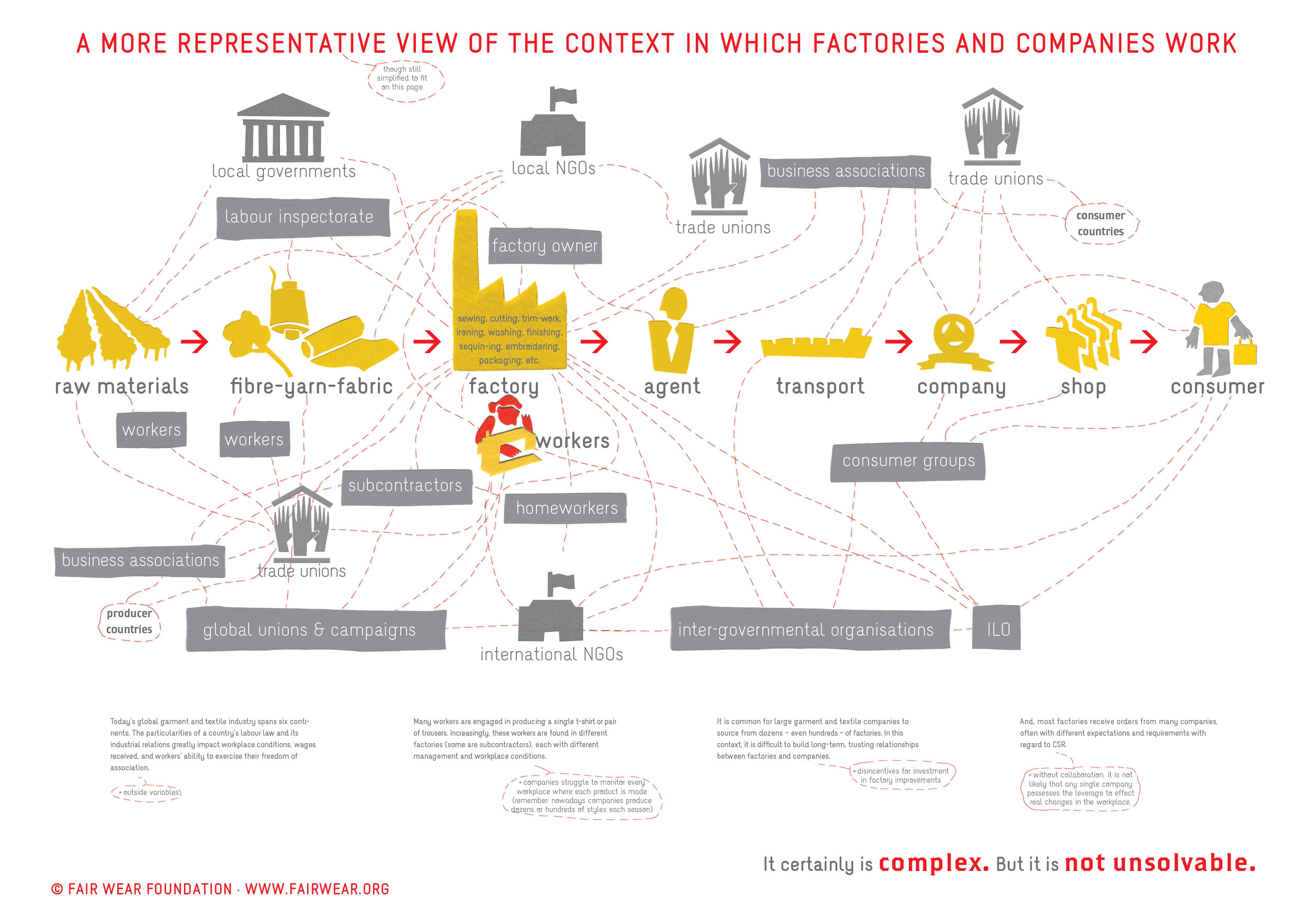

But many supply chains can be very complex. A typical global supply chain is complex, multi-layered and involves a wide range of organizations, suppliers and stakeholders.

For example, garment supply chains are often seen as being simple, although in practice they are not. In industries, such as garments, the lead companies – sometimes referred to as ‘brands’ – do not own any factories. The lead companies ‘outsource’ all production to independent factories. They may change suppliers from factory to factory each season, looking for lower prices or special skills. If lace shirts are in fashion one season and denim the next, brands source from a lace factory one season and a denim factory the next.

Lead companies engage in global supply chains in both direct and indirect ways, which often results in complex relationships or ‘arm’s length’ relations with the suppliers. (Meixell and Gargeya, 2005) Direct relations are formed through foreign direct investment, purchase of a specialist supplier or by establishing a new production facility in another country, where the task that is performed abroad remains within the ownership of the lead firm. However, increasingly, these tasks are carried out through outsourcing. This creates a contract relationship with an independent supplier, which can also occur indirectly, through the purchase of a production input from a domestic supplier that, in turn, receives some of its inputs from abroad.

This complexity of the global supply chain in garments is shown in Chart 2.

In these kinds of supply chains – which are very common in apparel and many other consumer goods – the responsibility to comply with legislation related to worker welfare and rights lies with the employing factories. However, the power to set prices, and to ensure they are high enough to allow decent working conditions, lies in part with the clothing brands. All factories have to comply with national labour laws and standards. Lead factories, however, have the power to influence labour conditions throughout their supply chains, by among others, through changes in price settings, corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices and adherence to ethical codes of conduct.

From the factory side, there are also forces that encourage fragmentation, especially in apparel. Many factories will choose to produce goods for many different brands. This reduces their risk of becoming too reliant on any one customer. For example, clothing factories do not have just one lead company - they may have 20 or 50 or 100. These buyers have significant power to influence a supplier’s capacity to respect workers’ rights, particularly as the large numbers of factories making nearly identical products (for example, t-shirts or trousers) means that competition – and pressure for low prices and fast production - can be very great.

Many low-income countries in the global South have promoted export-led growth and have become an increasingly important part of the global economy through their integration into supply chains. For example, agriculture-based economies in sub-Saharan Africa see horticulture as a key sector for economic growth, exports and employment for women. The growth of global supply chains (GSCs) in developing economies has been boosted by Export Processing Zones (EPZs) or Special Economic Zones (SEZs) offering a favourable business environment, including tax exemptions and free provision of infrastructure. EPZs have been set up in 130 economies for the processing of imported materials that are then re-exported to other countries. As a means to promote the export sector, in some cases, factories are specifically excluded from national labour and tax regulations, including the freedom to form and join a trade union.

According to Oxfam International (2004) globalization has resulted in trade policies that reinforce insecurity and vulnerability for millions of women workers. Oxfam’s research was carried out with partners in 12 countries, involved interviews with hundreds of workers (mostly women) and many farm and factory managers, supply chain agents, retail and brand company staff, unions and government officials. It revealed how retailers (supermarkets and department stores) and clothing brands are using their power in supply chains systematically to push many costs and risks of business on to producers, who in turn pass them on to workers, often women. In developed economies, women are also employed in precarious jobs in global supply chains, for example, in supermarkets and sports retailers.

The benefits of flexibility for companies at the top of global supply chains have come at the cost of precarious employment for those at the bottom. (Oxfam, 2004, p. 3)

Example: Peru and Colombia

In 1991, the US lifted the tariff on asparagus imports, opening an enormous new market for the premium vegetable, which the huge agro-exporters dominate.

The growing non-traditional agricultural export (NTAE) industries in Peru and Colombia – namely asparagus and cut flowers, respectively – are providing increased employment opportunities for women, particularly in rural areas, where other salaried jobs are scarce. However, recent research shows that the Andean governments’ numerous policies to promote the growth of the NTAE sector have not been matched with efforts to guarantee safety and quality of employment. It appears that recent labour reforms in Peru and Colombia have actually served to worsen working conditions and wages, while ensuring lower costs and increased flexibility for employers. (Ferm, 2008)

Relationships between buying and producing countries are often complex. In 1991, the US lifted the tariff on asparagus imports, opening an enormous new market for the premium vegetable, which the huge agro-exporters dominate. In 2000, legislation was passed in Peru to further encourage the growth of the asparagus industry. Tax on profits was reduced to half the national average, the minimum wage modified and an “accumulated workday” formula was introduced to allow employers to require a 20-hour workday. The law applied only to the female- dominated agro-industry sector. (Solidar, 2012)

Example: Electronics sector

The electronics sector is characterized by fluctuating orders, due to the short product cycles for electronic products and rapid obsolescence. This results in a high level of temporary and agency workers in some countries and high levels of overtime in others. In countries with a strong supplier base in electronics, domestic regulations have played a key role in determining how supply chain supplier firms react to production flexibility. In Mexico and Thailand there are large numbers of temporary workers; while in Malaysia and China there are high levels of overtime work. Chinese factories face a legal limit (since March 2014) restricting the number of temporary workers to no more than 10 per cent of the workforce. In India, the proportion of temporary, contractual and indirect wage employment accounted for just over 40 per cent in the industry. An estimated two-thirds of female workers in the electronics industry are in temporary, contractual or indirect wage employment. (ILO, 2015)

What is decent work?

Decent work gives people opportunities for:

- Promoting work: work that is productive and delivers a fair income.

- Guaranteeing rights at work: so that workers have well-being and security in the workplace.

- Social protection: to enjoy working conditions that are safe, allow adequate free time and rest, take into account family and social values, provide for adequate compensation in case of lost or reduced income and permit access to adequate healthcare.

- Promoting social dialogue: freedom for people to express their concerns, organize in trade unions and participate in the decisions that affect their lives.

- Equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men: including non-discrimination, equal pay for work of equal value, and maternity protection.

The ILO’s fundamental conventions are:

- Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87)

- Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98)

- Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29)

- Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105)

- Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138)

- Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)

- Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100)

- Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111)

For further information on the ILO’s Decent Work agenda see: http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/decent-work-agenda/lang--en/index.htm

Listen to the presentation from Professor Stephanie Barrietos, who talks about the complexity of global supply chains, including the fragmentation of work and of production in global supply chains. She argues that global supply chains have been beneficial to women and men in opening up new employment, but the downward pressure on costs has also resulted in a significant increase in precarious work, particularly for women. She discusses the role that the ILO is playing in improving labour standards in global supply chains and in promoting alliances. See: http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/multimedia/video/video-interviews/WCMS_382039/lang--en/index.htm